Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

2025-10-15

Housekeeping

- Coding practice due tonight

- Midterms returned tomorrow!

Bootstrap recap

Sampling distribution describes how statistic behaves under repeated sampling from population

Typically cannot repeatedly sample from population, so we obtain bootstrap distribution as approximation of the sampling distribution of the statistic!

- Assume we have a sample \(x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}\) from the population. Call this sample \(\boldsymbol{x}\). Note the sample size is \(n\)

- Choose a large number \(B\). For \(b\) in \(1,2, \ldots, B\):

- Resample: take a sample of size \(n\) with replacement from \(\boldsymbol{x}\). Call this set of resampled data \(\boldsymbol{x}^*_{b}\)

- Calculate: calculate and record the statistic of interest from \(\boldsymbol{x}^{*}_{b}\)

At the end of this procedure, we will have a distribution of resample or bootstrap statistics

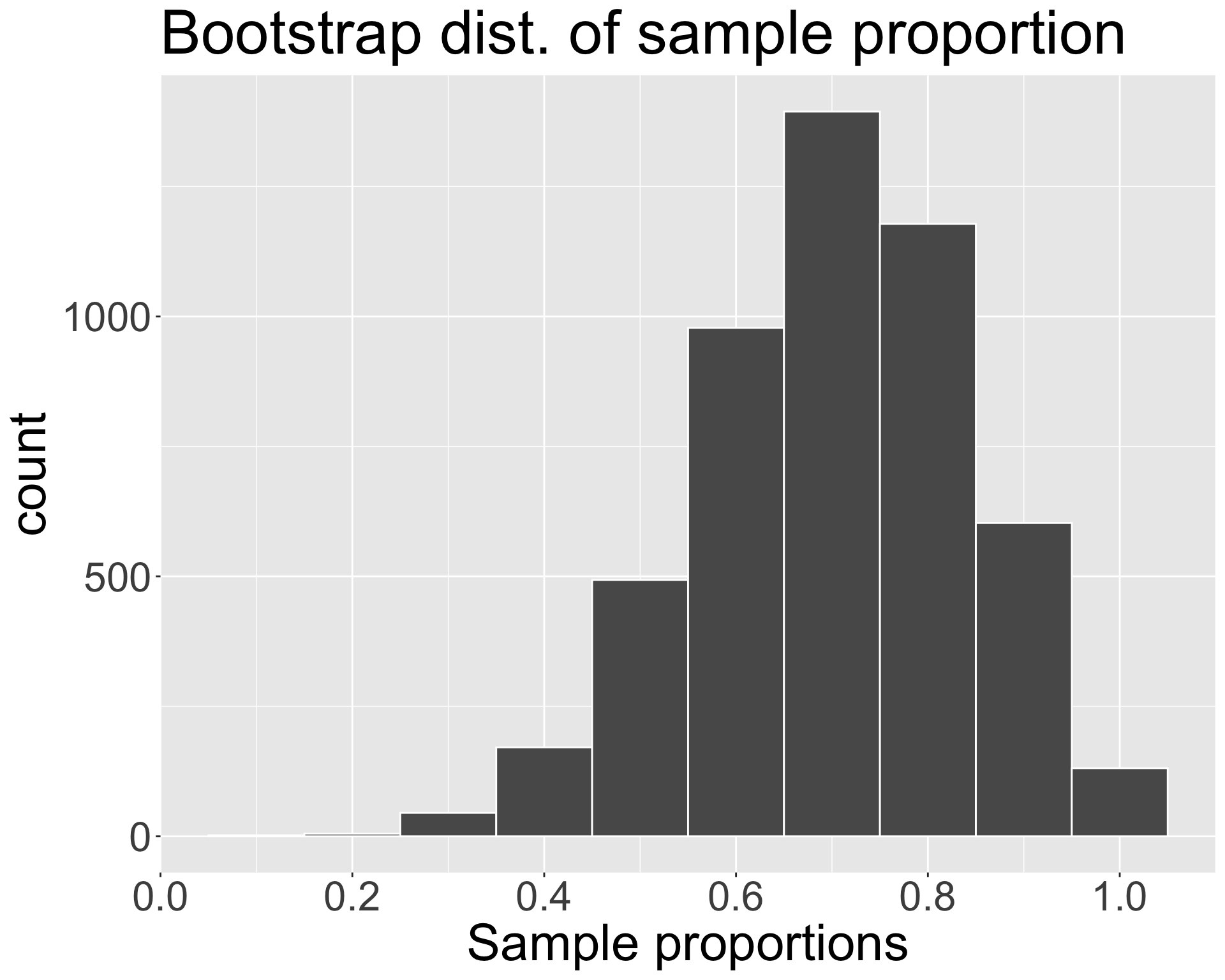

Bootstrap distribution from activity

In our original sample of \(n = 10\), we had \(\widehat{p_{obs}} = 0.7\).

We have the following bootstrap distribution of sample proportions, obtained from \(B=\) 5000 iterations:

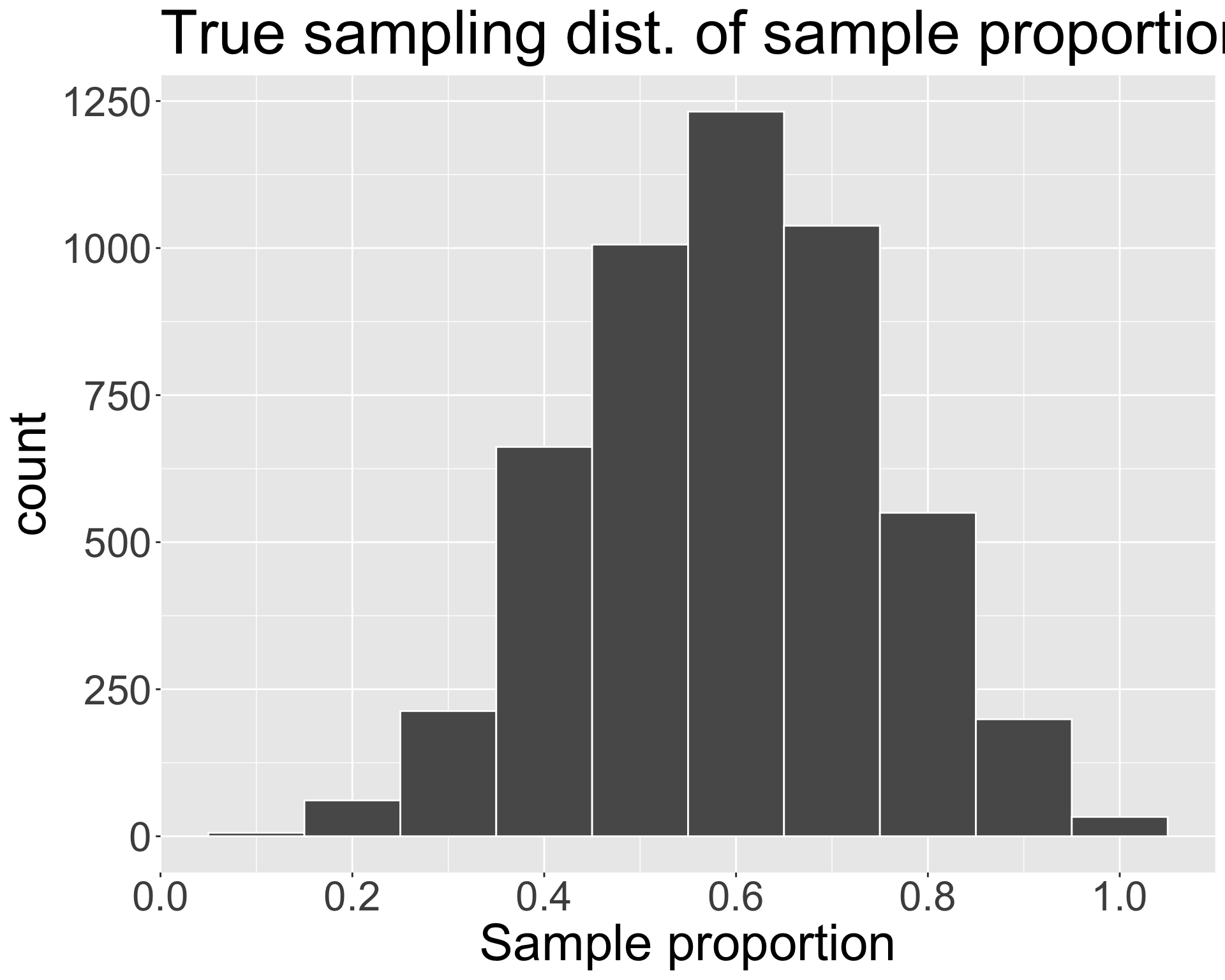

We can compare to the true sampling distribution (because it’s easy for me to re-sample from the population here):

- Notice that our bootstrap distribution isn’t a great approximation (maybe \(n = 10\) did not yield a representative sample)

Answering estimation question

Great…but what do we do with the bootstrap distribution?

Recall our research question: What proportion of STAT 201A pronounced as Middle-“berry”?

Could respond using our single point estimate: \(\hat{p_{obs}} = 0.7\)

But due to variability, we recognize that the point estimate will rarely (if ever) equal population parameter

Rather than report a single number, why not report a range of values?

This is only possible if we have a sampling distribution to work with!!

Confidence intervals

Analogy: would you rather go fishing with a single pole or a large net?

- A range of values gives us a better chance at capturing the true value

A confidence interval provides such a range of plausible values for the parameter (more rigorous definition coming soon)

“Interval”: specify a lower bound and an upper bound

Confidence intervals are not unique! Depending on the method you use, you might get different intervals

Bootstrap percentile interval

The \(\gamma \times 100\)% bootstrap percentile interval is obtained by finding the bounds of the middle \(\gamma \times 100\)% of the bootstrap distribution

Called “percentile interval” because the bounds are the \((1-\gamma)/2\times100\) and \((1+\gamma)/2\times 100\) percentiles of the bootstrap distribution

- If \(\gamma = 0.90\), then the bounds would be at which percentiles?

- For our purposes, “bootstrap confidence interval” will be equivalent to “bootstrap percentile interval”

quantile()function inRgives us easy way to obtain percentiles:quantile(x, p)gives us \(p\)-th percentile ofx

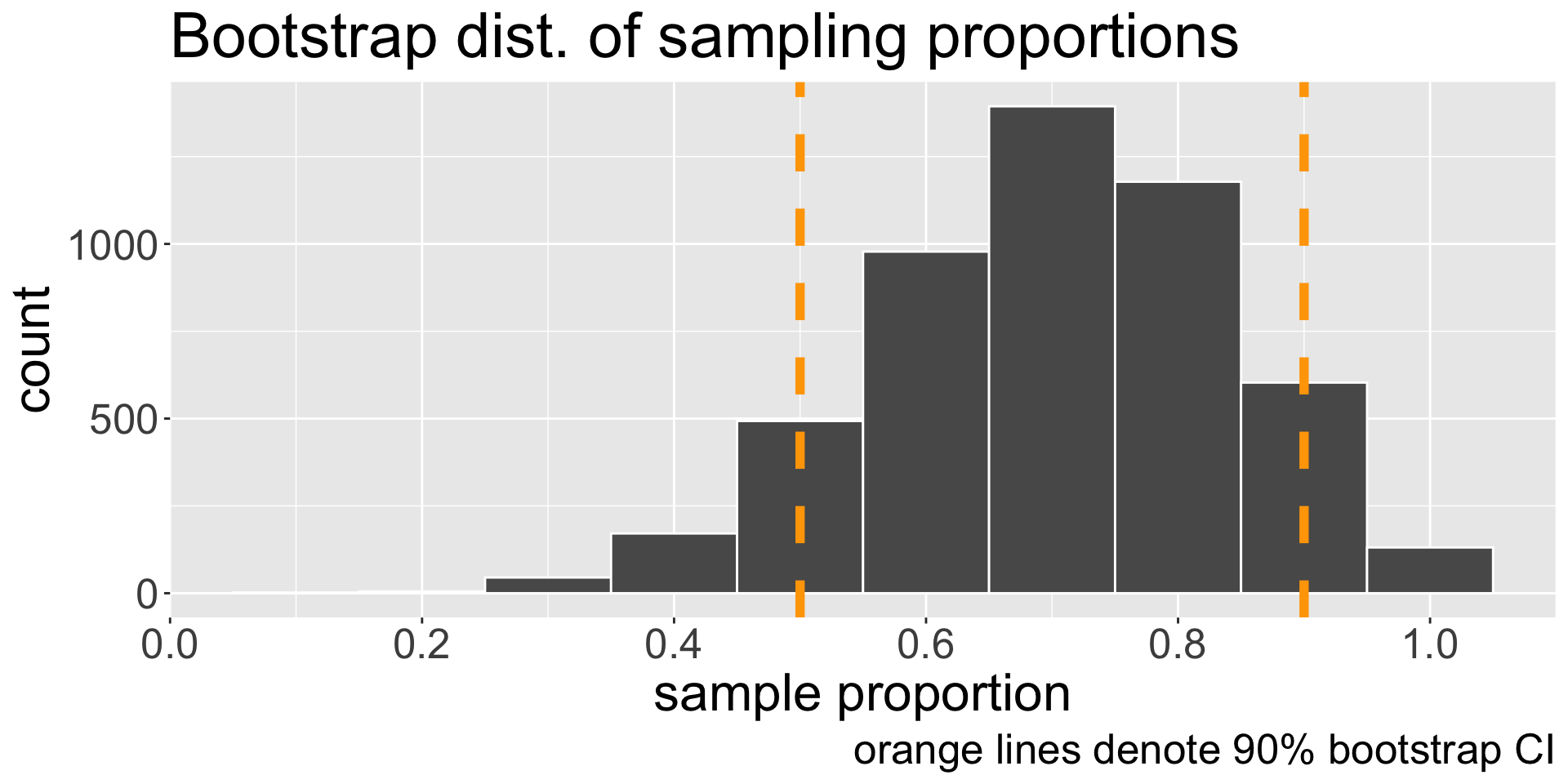

Visualizing bootstrap confidence interval

- Our 90% bootstrap CI for \(p\): (0.5, 0.9)

Interpreting a confidence interval

Our 90% bootstrap CI for \(p\): (0.5, 0.9). Does this mean there is a 90% chance/probability that the true proportion lies in the interval?

Answer: NO

Remember: bootstrap distribution is based on our original sample

- If we started with a different original sample \(\boldsymbol{x}\), then our estimated 90% confidence interval would also be different

What a confidence interval (CI) represents: if we take many independent repeated samples from this population using the same method and calculate a \(\gamma \times 100\) % CI for the parameter in the exact same way, then in theory, \(\gamma \times 100\) % of these intervals should capture/contain the parameter

\(\gamma\) represents the long-run proportion of CIs that theoretically contain the true parameter

However, in real life we never know if any particular interval(s) actually do!

Interpreting a confidence interval (cont.)

Correct interpretation (generic) of our interval \((a,b)\): We are \(\gamma \times 100\) % confident that the population parameter is between \(a\) and \(b\).

Interpret our bootstrap CI in context

Again: why is this interpretation incorrect? “There is a 90% chance/probability that the true parameter value lies in the interval.”

- True proportion from census is \(p = 0.593\)

Remarks

What is a virtue of a “good” confidence interval?

How do you expect the interval to change as the original sample size \(n\) changes?

How do you expect the interval to change as level of confidence \(\gamma\) changes?

- Once again, a good interval relies on a representative original sample!

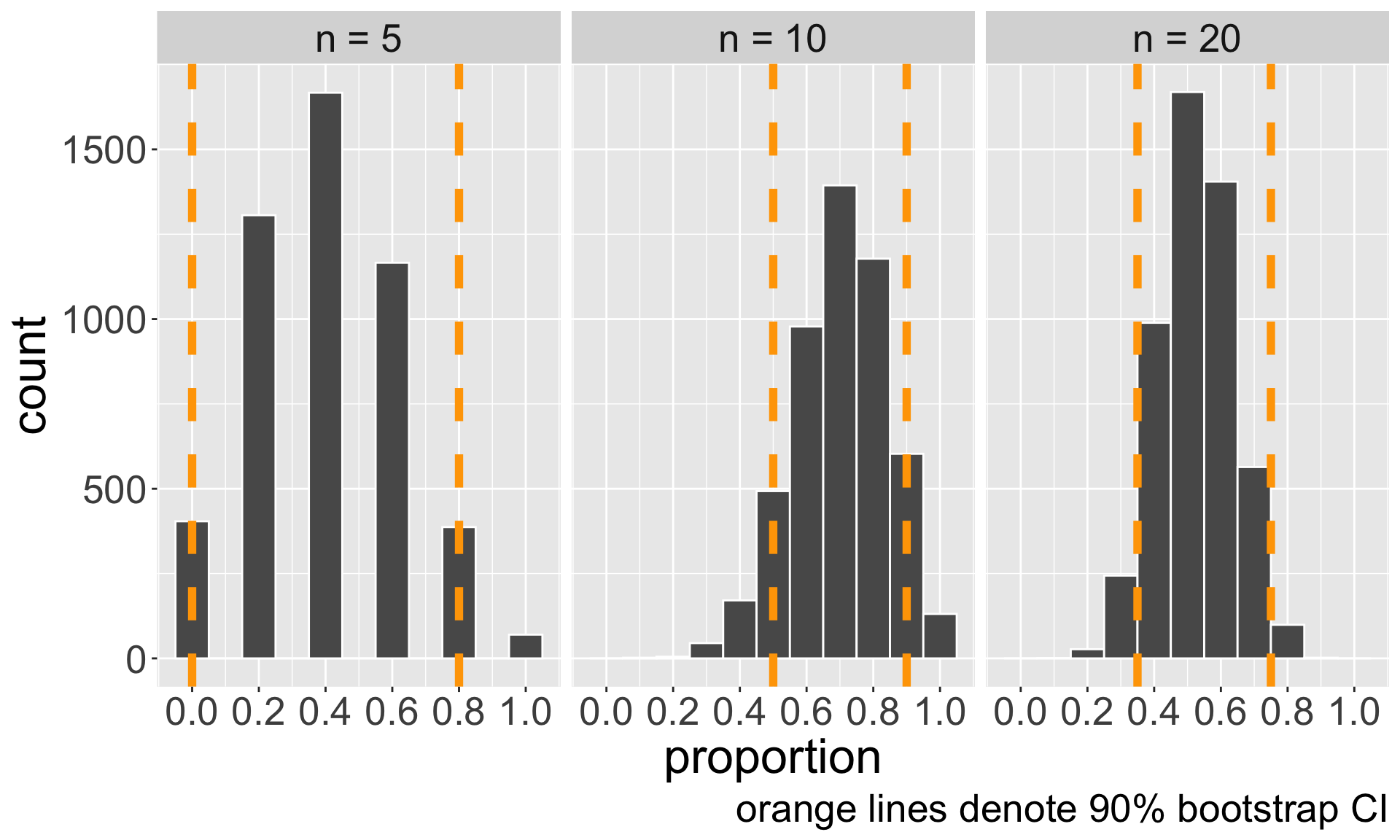

Comparing confidence intervals

Comparing changes in 90% bootstrap CI for sample sizes \(n = 5, 10, \text{ and } 20\).

| n | interval |

|---|---|

| n = 5 | (0, 0.8) |

| n = 10 | (0.5, 0.9) |

| n = 20 | (0.35, 0.75) |

What do you notice about the bootstrap distributions and CIs as \(n\) increases?

Live code + Coding practice!

Live code:

in-line code

setting a seed

You will investigate what happens as we move \(\gamma\) between \(0\) to \(1\)!

In-line code

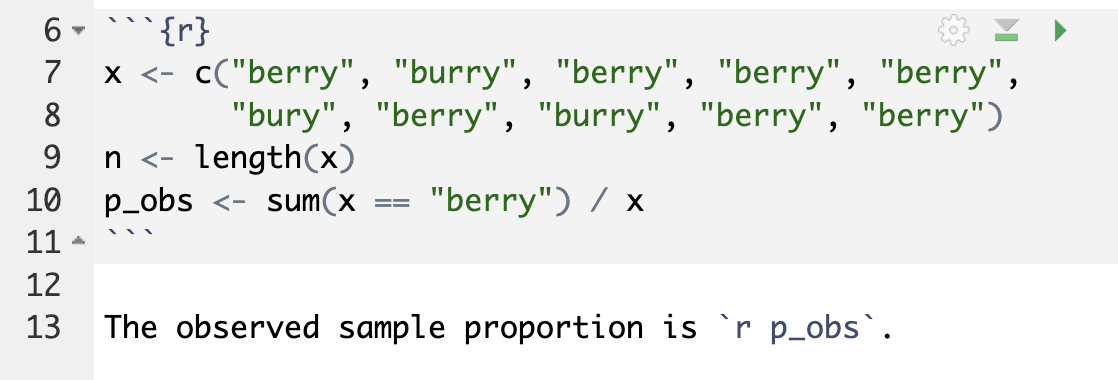

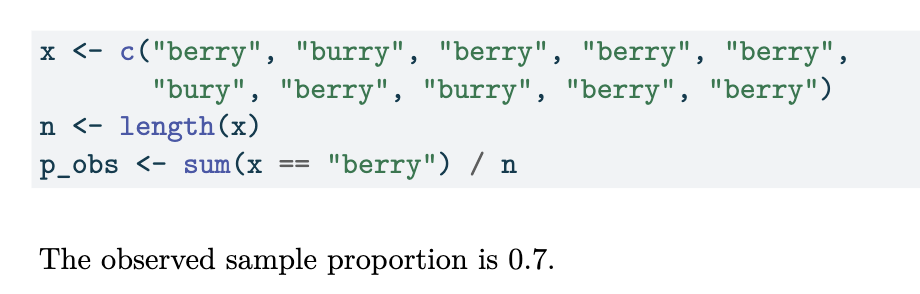

In-line code allows us to be reproducible! Suppose I do all this analysis:

[1] 0.7I might want to report this value! Rather than “hard-code” the value 0.7 in the white text of my .qmd, I want the .qmd to update the value dynamically upon rendering!

.qmd file

Rendered PDF

- Notice the syntax of inline code! Backticks, r, and the spacing matter!

Setting a seed

When we do random sampling, how can we reproduce our results? By setting a seed!

- “Random” sampling is achieved via a “random number generating function”, which takes in a number as input. Kind of like initializing the randomness.

set.seed(<integer>)before doing random sampling will initialize the generator at that specificintegerinput, so subsequent calls to random number generating functions will produce the exact same sequence of “random” numbers