Hypothesis testing for a mean

2025-10-23

Housekeeping

- Make sure to start working on Problem Set 6!

Recap

We have seen how to perform hypothesis tests for questions involving the following:

A single proportion (Middle “berry” vs “burry”)

Independence of two categorical variables (banker sex discrimination)

- Think of as one population

Difference in two proportions (blood thinner)

- Think of as two populations

We are now going to see another hypothesis test, this time for numerical data

Test for a single mean

Running example + form hypotheses

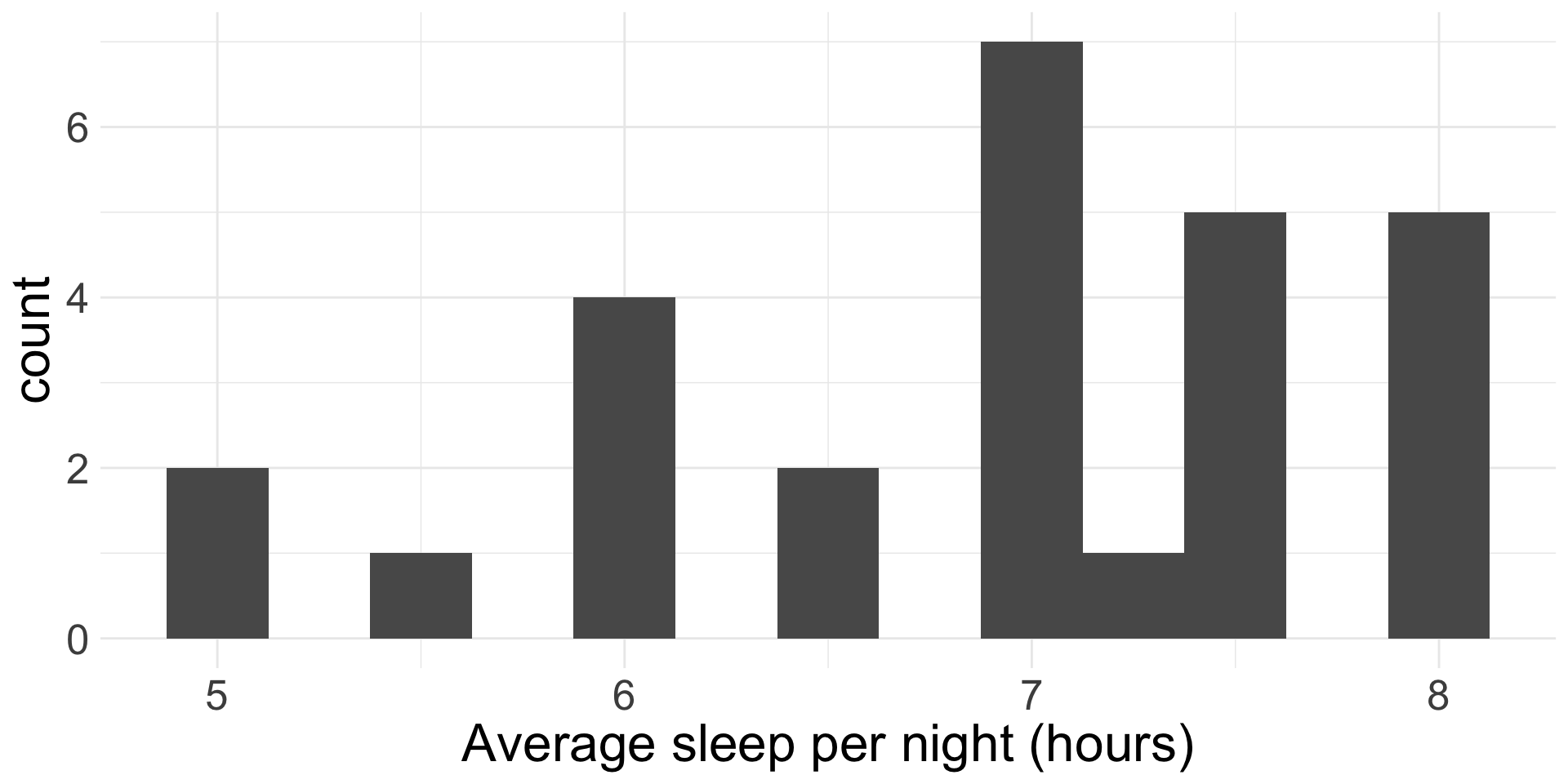

We will use the the data I collected from you about average hours of sleep per night.

What type of variable(s) do we have?

- I know most college students don’t receive the recommended 8 hours of sleep. But what about 7.5 hours?

Before we look at the data, we should form our hypotheses. Suppose I am interested in learning if Middlebury students who have an 8:15am class get at most 7.5 hours of sleep (on average).

What might our hypotheses be?

- \(H_{0}\): \(\mu =\) 7.5 versus \(H_{A}\): \(\mu <\) 7.5, where \(\mu\) is the true mean of the average hours of sleep Middlebury students with an 8:15 am class get.

- Terminology: I will refer to \(\mu_{0} =\) 7.5 as my “null hypothesized value”. (i.e. the specific value of \(\mu\) in \(H_{0}\))

- \(H_{0}\): \(\mu =\) 7.5 versus \(H_{A}\): \(\mu <\) 7.5, where \(\mu\) is the true mean of the average hours of sleep Middlebury students with an 8:15 am class get.

Collect and summarise data

The observed/sample mean of average hours of sleep per night is \(\bar{x}_{obs} =\) 6.896 from a sample of 27 students

- Now we must determine if we have “convincing evidence”! Choose \(\alpha = 0.05\)

Simulating null distribution

To simulate from the null distribution, we need to operate in a world where \(H_{0}\) is true.

So, I need to repeatedly simulate data sets of size 27 where true mean is \(\mu_{0} =\) 7.5, without changing anything else

- Specifically, my hypotheses aren’t saying anything about spread, just center!

If I don’t want to make any assumptions about how the data behave, how might I do that?

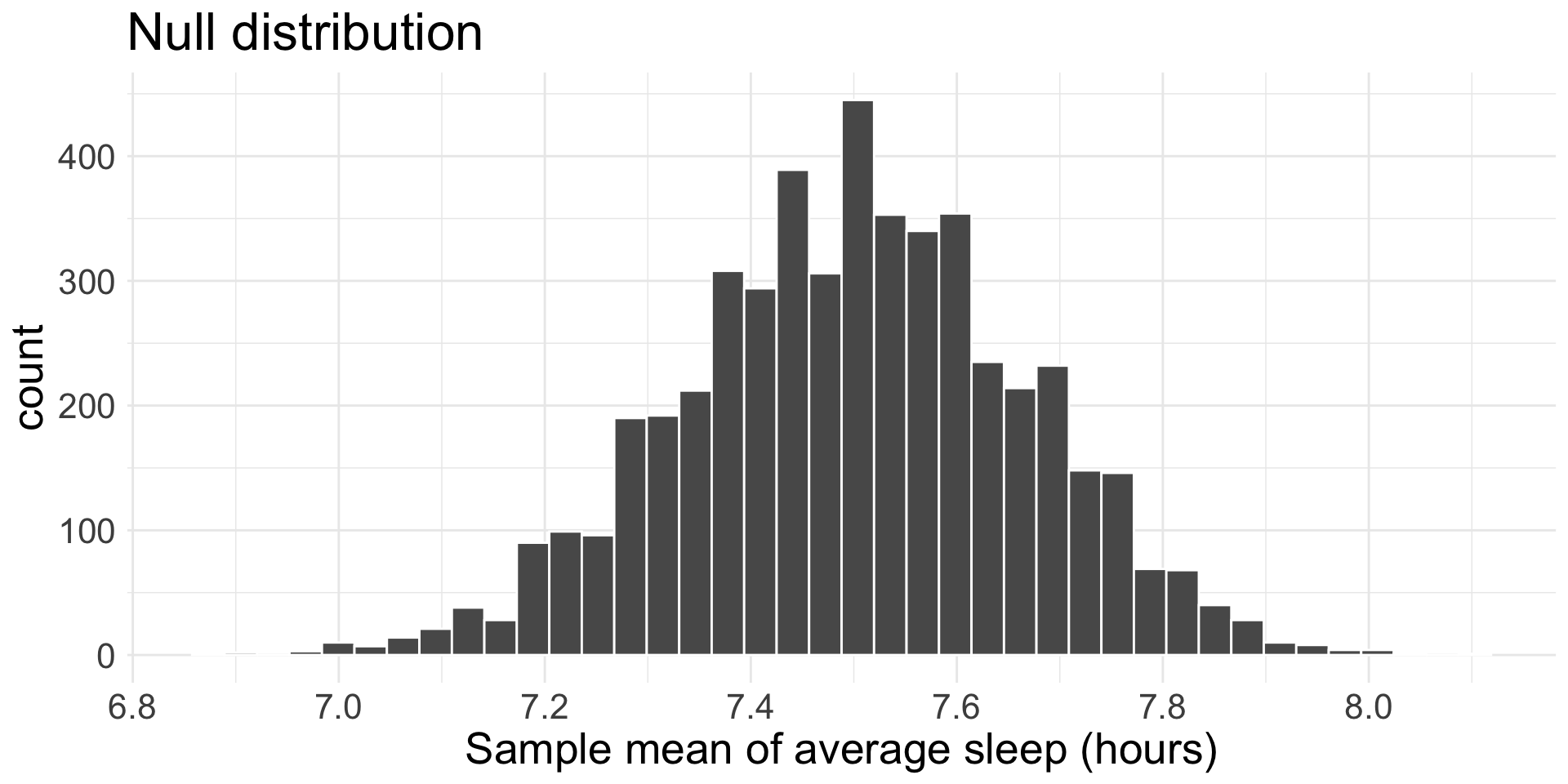

Recap bootstrap (NOT exactly the strategy)

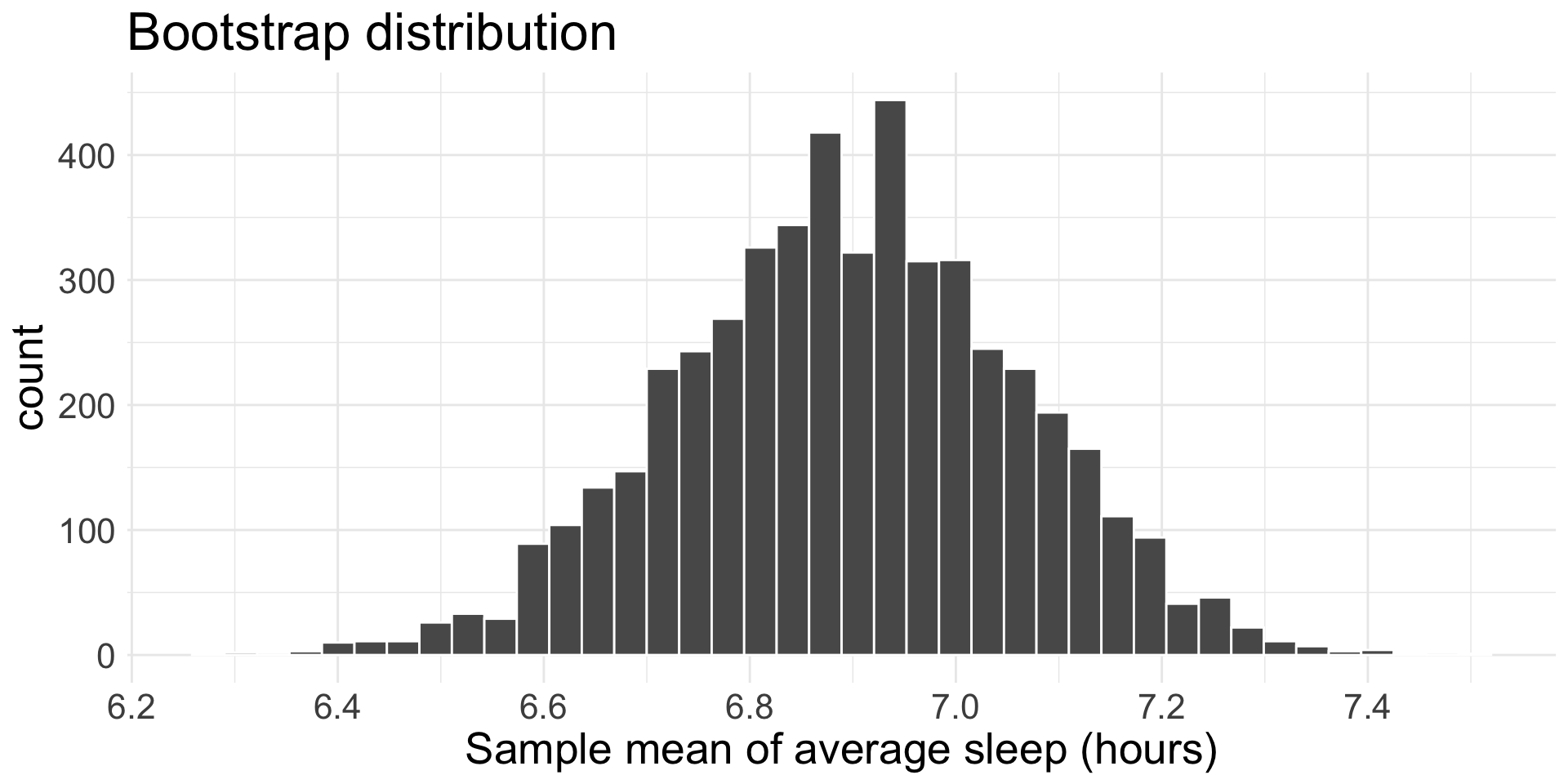

How would I obtain a bootstrap distribution of the sample mean of mean hours of sleep?

Remind ourselves: Where should the bootstrap distribution be centered?

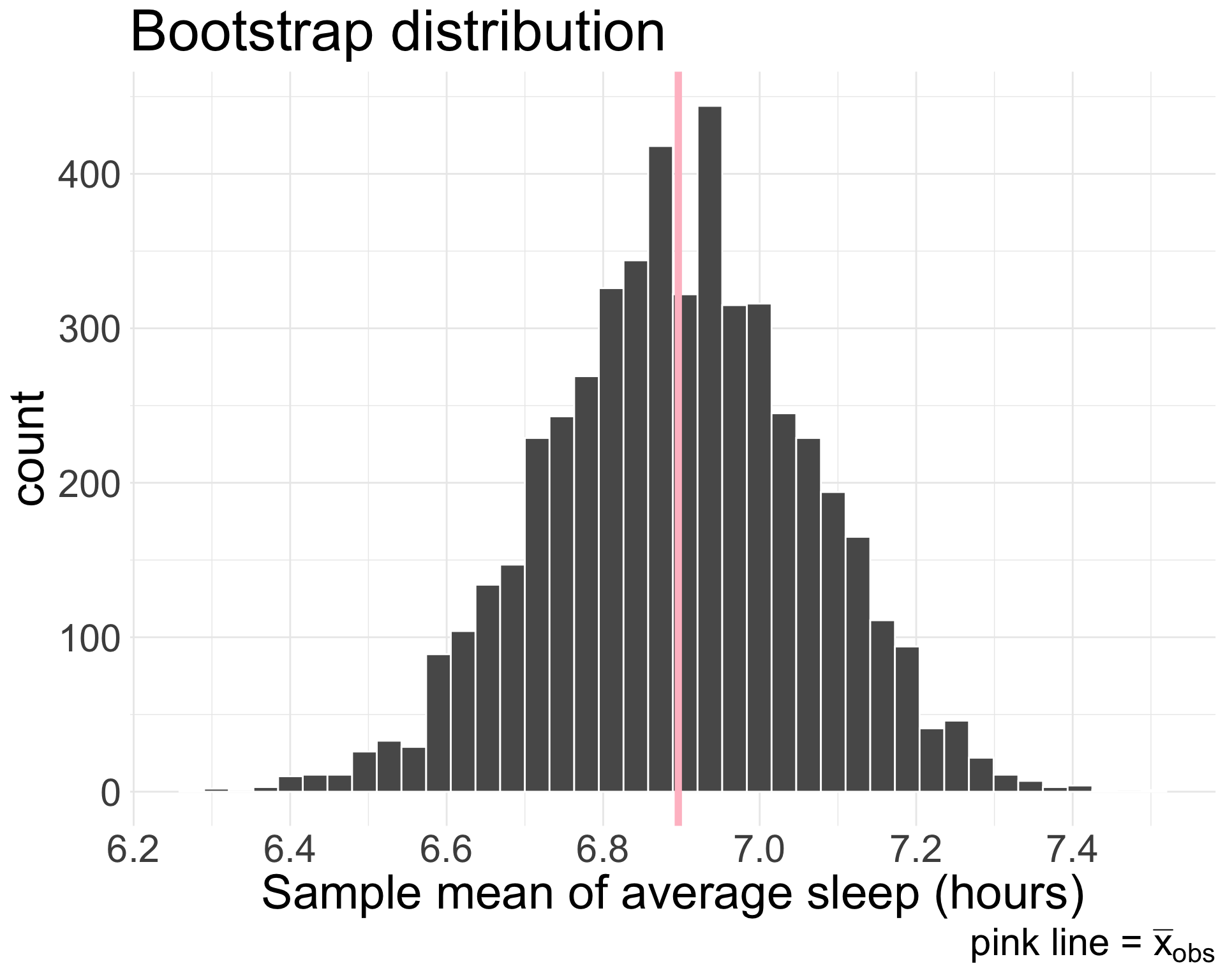

Bootstrap to null distribution

This is not the null distribution! The null distribution should be centered at \(\mu_{0} = 7.5\)

However, the null distribution should have the same variability in \(\bar{x}\) as the bootstrap distribution.

- So to get the null distribution, why not just shift the bootstrap distribution to be centered where we want it to be?

Shifting the bootstrap distribution

In this example, bootstrap distribution is centered at \(\bar{x}_{obs} = 6.896\)

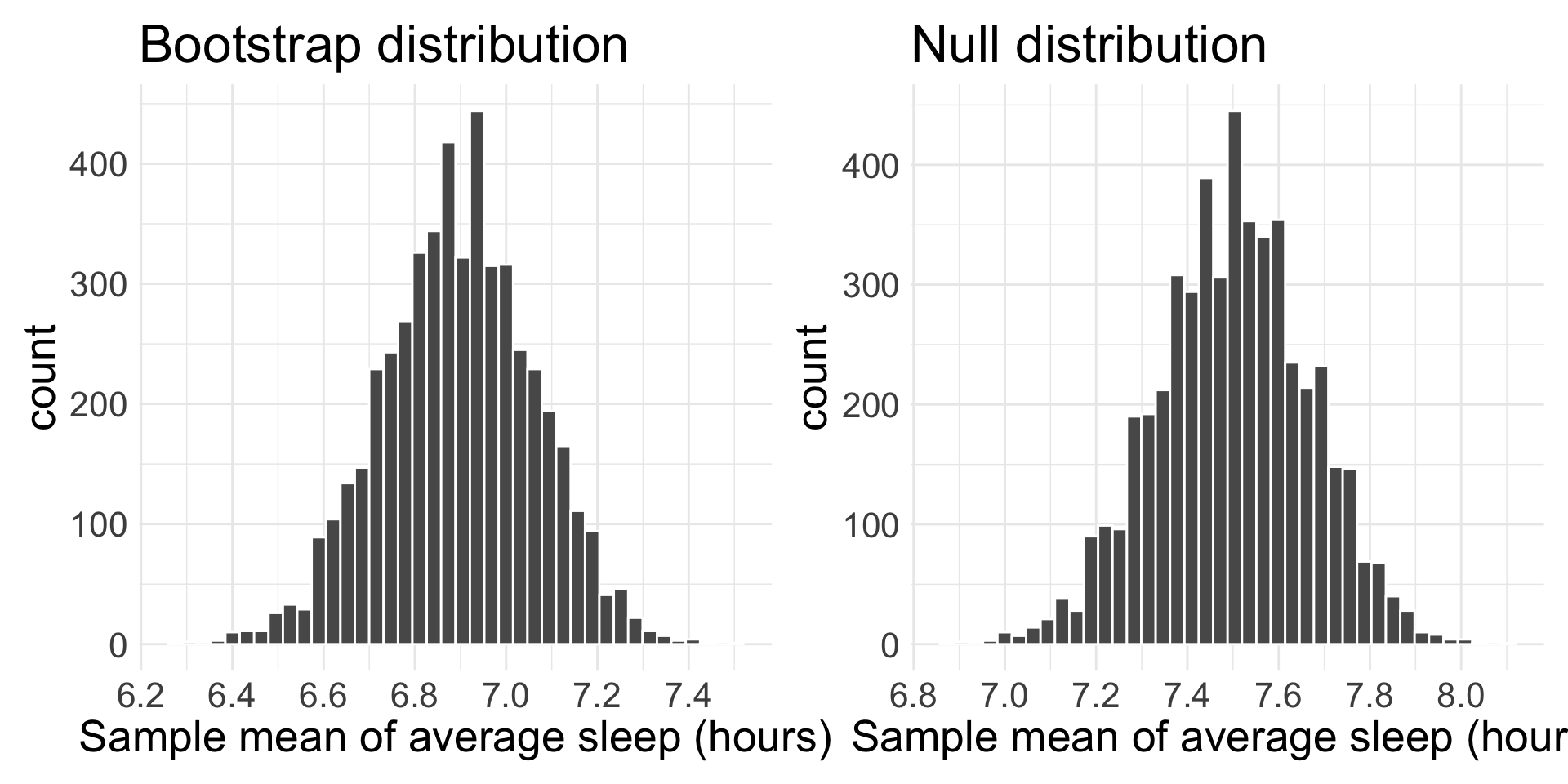

In order to center this distribution at \(\mu_{0} = 7.5\), just subtract \(6.896 - 7.5 = -0.604\) from every single bootstrapped mean

This will give us a simulated distribution for \(\bar{x}\) centered at \(\mu_{0} = 7.5\), which is exactly the null distribution!

We call this “shifting the bootstrap distribution”, because we simply shift where the bootstrap distribution is centered

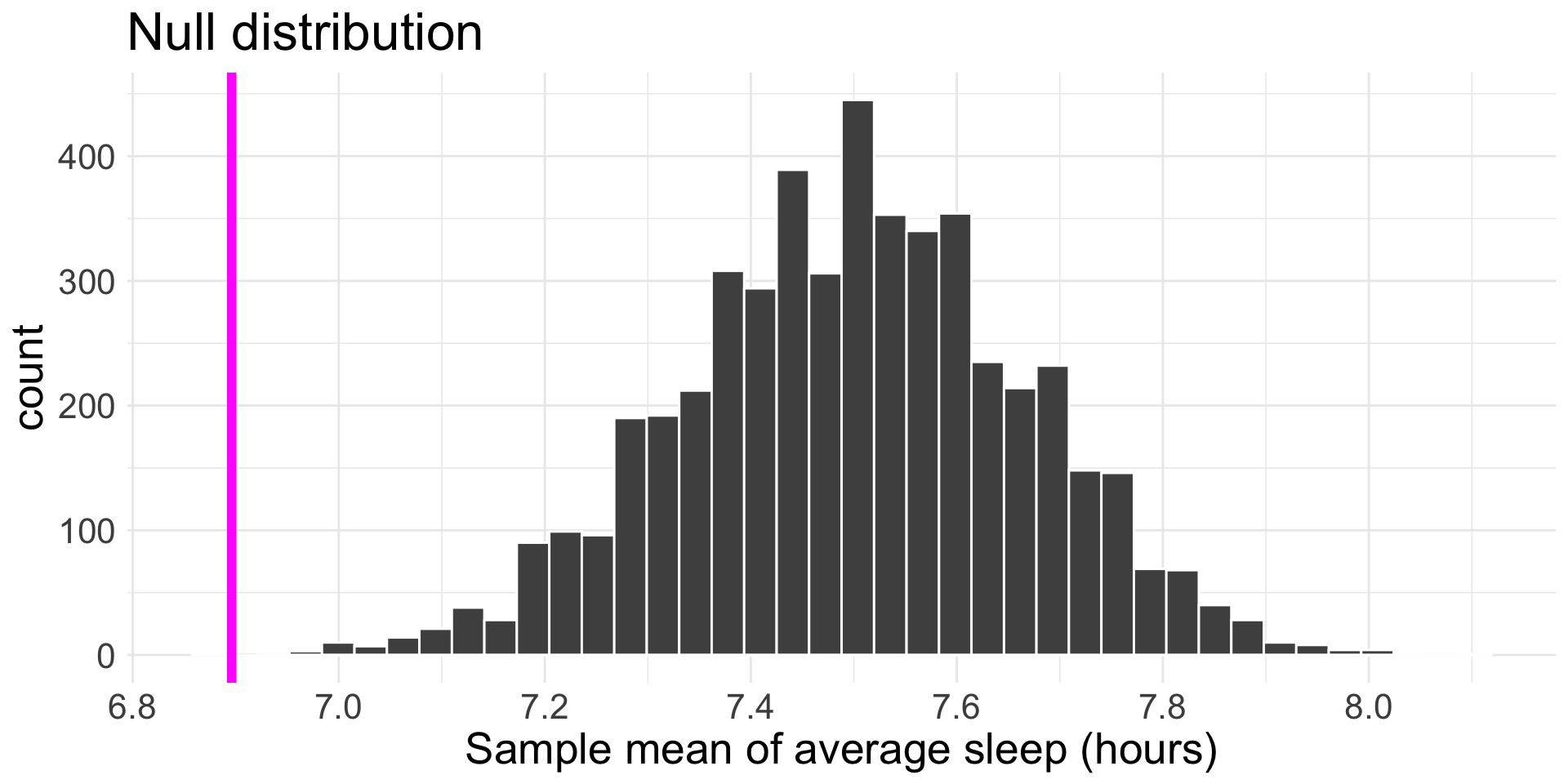

Null distribution

Notice where the distributions are centered. Also note: graphs aren’t exactly identical due to binning of histogram.

Obtain the p-value

\(H_{0}\): \(\mu =\) 7.5 versus \(H_{A}\): \(\mu <\) 7.5

Our observed sample mean is \(\bar{x}_{obs} =\) 6.896.

How do we find our p-value?

- In 5000 iterations, simulated 1 “as more extreme” than our data, so p-value is approximately 0.0002.

Make decision and conclusion

Make a decision and conclusion in the context of the research question.

- Since our p-value of 0.0002 is less than the significance level of 0.05, we reject \(H_{0}\). We have convincing evidence to suggest that the true mean of the average hours of sleep per night that a Middlebury student with an 8:15am course receives per night is less than 7.5 hours.

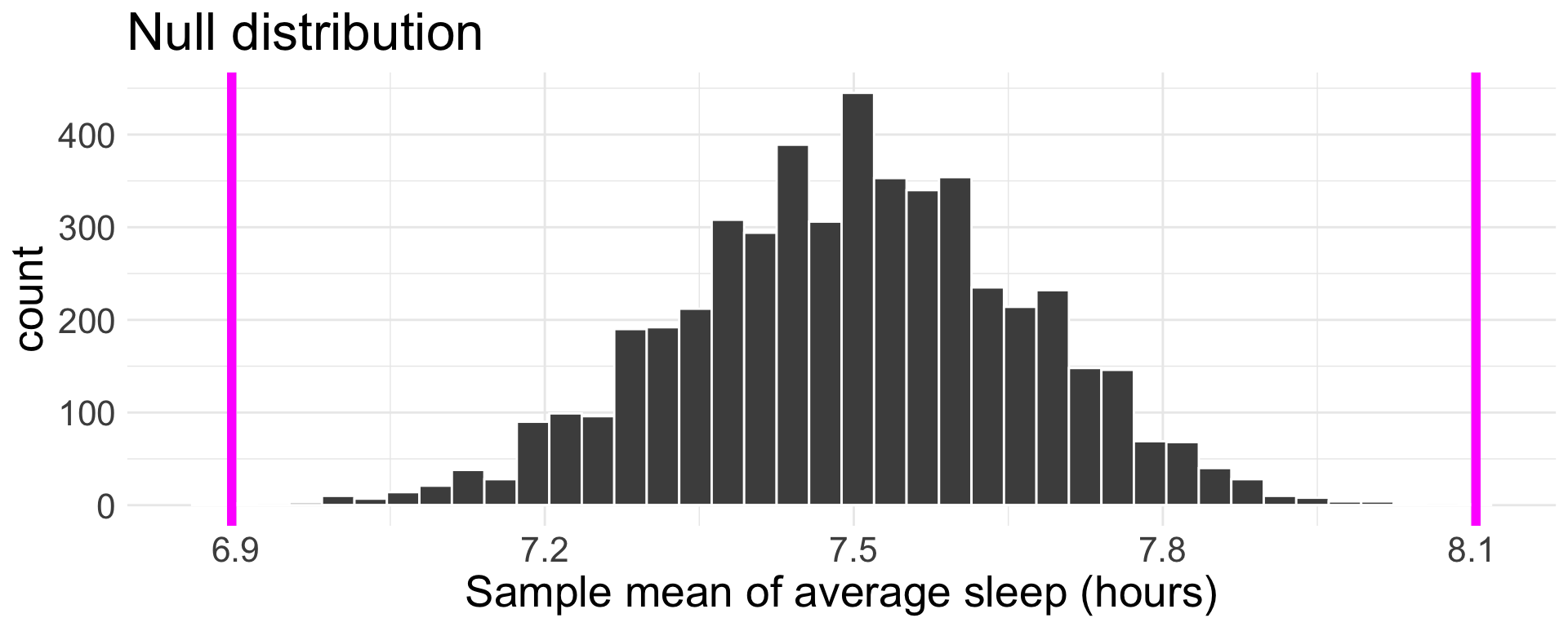

Two-sided alternative hypothesis

What if instead, I am interested in learning if Middlebury students who have an 8:15am class get 7.5 hours of sleep or not (on average). Then our hypotheses are:

\[H_{0}: \mu = 7.5 \qquad \text{ vs. } \qquad H_{A}: \mu \neq 7.5\]

- What does it mean to be “as or more extreme” now? Remember, \(\bar{x}_{obs} = 6.896\)

Two-sided alternative hypothesis

We can be extreme in both the positive and negative direction of \(\mu_{0}\)!

- Note that there are now 2 simulations that are “as or more extreme”, so p-value is approximately 0.0004.

Obtain the p-value (cont.)

Let \(shift\) represent the amount we shifted the bootstrap distribution by:

\[shift = 6.896 - 7.5 = -0.604\]

Simulated sample means as or more extreme as the following will contribute:

\(\mu_{0} + shift = 7.5 + -0.604 = 6.896\) , or

\(\mu_{0} - shift = 7.5 - -0.604 = 8.104\)

Note that how you code will depend on if shift is positive or negative. That’s why it’s important to summarise your data in step 2!

Make decision and conclusion

Make a decision and conclusion in the context of the research question.

- Since our p-value of 0.0004 is less than the significance level of 0.05, we reject \(H_{0}\). We have convincing evidence to suggest that the true mean of the average hours of sleep per night that a Middlebury student with an 8:15am course receives per night is different from 7.5 hours.

Comprehension questions

Why did we shift the bootstrap distribution?

Why can’t we simulate null world like we did in the case of proportions?

How does the p-value from a two-sided \(H_{A}\) compare to that of a one-sided \(H_{A}\)?

How is this different from the homework problem where you’re comparing two means?